Corporate Signatures: Why Disclosing Corporate Titles Protects Real Estate Officers

| Footnotes for this article are available at the end of this page. |

Corporate officers execute many written contracts, but a single misstep in execution can shift liability from the company to the individual signatory. For a corporate agent, failing to properly disclose his or her office when signing on behalf of a company can result in the signature being treated as a personal one, exposing the officer to liabilities, debts, and obligations that were never intended to be theirs. This is not a theoretical risk; courts across the country have held signatories personally liable when their representative capacities are unclear in a written contract. Thus, ensuring that a signature unambiguously reflects the agent’s corporate role is a simple but essential step to limit personal liability.

This article examines corporate officer signature requirements under state law, highlights why real estate professionals should be especially vigilant, and outlines practical steps to minimize personal risk.

Understanding State Law on Corporate Officers’ Signatures

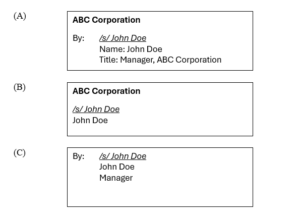

Most states provide that a corporate representative’s signature does not create personal liability if the form of the signature shows unambiguously that the representative is acting on behalf of the company identified in the contract. Consider the following signature blocks:

|

The three signature blocks may appear similar, but the legal consequences differ significantly. In signature block (A), the signatory stated that ABC Corporation’s execution was “By” the agent and listed his office within the company. Signature block (A) unambiguously shows that manager John Doe is acting on behalf of ABC Corporation, retaining the limited liability afforded to corporate officers.1

On the other hand, in signature block (B), no company role is listed next to the signatory. Accordingly, personal liability for manager John Doe under the agreement depends on a court’s interpretation of whether the failure to indicate his office in the company renders the representative capacity of the signing party ambiguous. For example, in Leahy v. McManus, the chairman of a company’s board of directors signed a promissory note directly below the company’s stamped name.2 The chairman failed to designate his role when signing the note but later argued that he signed the note in his representative capacity3 Because he did not disclose his role within the company in his signature, the Court of Appeals of Maryland found that “there was ambiguity in the evidence as to the circumstances under which the note was executed,” but ultimately found that the case-specific facts showed that the payee understood the chairman had signed in his representative capacity.4

Finally, in signature block (C), even though John Doe lists that his role is “manager,” the signature does not include the name of the principal company. In this circumstance, the representative capacity of the signing party is left to a court’s interpretation because it does not identify the company undertaking the contract. This played out in the Louisiana case Fidelity National Bank v. Red Stick Wholesale Music Distributors, Inc., where a corporate officer was found personally liable for the unpaid balance of a promissory note. The company signed the front of the note, and the officer signed the reverse of the promissory note as “president.” However, he failed to identify the company on whose behalf he was purporting to sign the note.5 Given the promissory note’s ambiguity, the court reasoned that the inclusion of “president” was “not used to describe the representative character in which the signature was affixed.”6

Georgia and New York: Two Outliers

In Georgia, personal liability risk to corporate officers increases. O.C.G.A. § 10-6-86 provides that an agent who signs a contract without identifying that they are signing in a representative capacity shall undertake personal liability for the contract. Georgia’s rule leaves little room for discretion, and it has been enforced consistently in Georgia Courts.

For example, in Griffin v. Associated Payphone, a company president was sued for breach of contract in his individual capacity because he signed the contract directly above the company’s name with “no indication near his signature of [his] office or position in the corporation.”7 The Georgia Court of Appeals determined that, although the company’s president “might have intended to sign the contract in his representative capacity only, he failed to limit his personal liability under the contract by showing his corporate office when he signed.”8

Similarly, in Talmadge v. Respess, two company representatives were sued individually for money due under a promissory note.9 Although the individuals claimed to have signed the note as representatives of a company, and even executed the note underneath the company name, the Georgia Court of Appeals recognized that “neither signature indicated that the individual executed the note in a representative capacity” and held that “it is the form of the signature on the note, and not other printed information appearing on the page, that governs the capacity in which the signer executes the note.”10 Accordingly, the court upheld a grant of summary judgment against both individuals on the note, rendering them personally liable and underscoring the importance of unambiguously including a title or otherwise indicating a representative capacity when signing on behalf of a company.

New York takes the opposite approach. In New York, the risk of personal liability is limited to instances only where the contract neither names the company represented nor shows that the representative signed in a representative capacity. N.Y.U.C.C. Law § 3-403(2). For example, in Salzman Sign Company v. Beck, the claimant sought payment under a sales contract from the president of a company, arguing that the president had signed the contract both on behalf of the company and individually.11 In the contract, the president had signed underneath the company’s name and indicated he was the “pres” of the company.12 The court found that this was still a corporate signature because, under New York law, a representative “will not be personally bound unless there is clear and explicit evidence of the agent’s intention to substitute or superadd his personal liability for, or to, that of his principal.”13 In contrast to other states’ laws, the court acknowledged that “there is great danger in allowing a single sentence in a long contract to bind individually a person who signs only as a corporate officer.”14

Commercial Real Estate Professionals Should Be Especially Wary

Although the principle of clearly disclosing a representative capacity applies across all corporate forms, those in commercial real estate should exercise extra caution because of the unique risks real property presents. Real estate transactions can include significant financial obligations, long-term leases, and liability for property conditions, such as premises liability, negligence, and common area maintenance. These stakes mean that an ambiguity or mistake in an agent’s signature block can expose the agent to personal liability for distant properties or acts far beyond his or her control. Given this risk, corporate agents in real estate should take extra care to unambiguously indicate their role within a company each time they sign a contract on a company’s behalf.

Best Practices

To avoid personal liability when signing agreements on behalf of a company, corporate agents should implement these best practices in future deals:

- Always use the full legal name of the company when signing agreements to ensure there is no ambiguity about the principal on whose behalf the agent is acting.

- Clearly disclose the agent’s proper role in the principal company next to, or directly under, the agent’s signature to show that he or she is signing in a representative capacity.

- Precede any signature with words like “By” or “Per” to explicitly indicate that the signature is on behalf of the company.

- Review signature blocks before signing to confirm that the agent’s title and the company’s name are properly included and formatted to avoid ambiguity.

- If there is any uncertainty about potential liability or unusual contract terms, seek guidance from legal counsel before signing.

If you have any questions about the effect of corporate signatures on your real estate transactions, please contact any member of the AGG Real Estate Litigation team.

[1] See Boyden v. HLS II, LLC, where the Eastern District of Pennsylvania found a representative was not individually liable under a promissory note because her signature block unambiguously showed her representative capacity, with the company listed as the “entity,” her name printed below, and her signature appearing on the line designated for her as vice president of the company. No. 18-3283, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 110920, at *4 (E.D. Pa. July 2, 2019) (interpreting Pa. U.C.C. § 3402).

[2] 237 Md. 450, 452 (1965).

[3] Id.

[4] Id. at 455. These facts included payee’s relationship to the company as stockholder and director; the fact that another officer, whose signature was required to bind the company, had also signed; and payee failed to attempt to hold the chairman personally liable for four years.

[5] 423 So. 2d 15, 16–17 (La. Ct. App. 1982) (interpreting La. R.S. 10:3-403 which reads: “Unless the instrument clearly indicates that a signature is made in some other capacity it is an indorsement.”).

[6] Id. at 17.

[7] 244 Ga. App. 183, 183–84 (2000).

[8] Id. at 184.

[9] 224 Ga. App. 768 (1997).

[10] Id. at 770 (quoting Avery v. Whitworth, 202 Ga. App. 508, 509 (1992)) (citations modified).

[11] 10 N.Y.2d 63, 65 (1961).

[12] Id.

[13] Id. at 67 (citation modified).

[14] Id.

Related Services

Related Industries

- Natalie L. Cascario

Associate

- Sydney J. Selman

Associate